When I found out that Laurie Anderson, multimedia artist and avant-pop icon, was nominated for a GRAMMY© in the Best Pop Instrumental Performance category, I was intrigued. I know, I’m supposed to be covering the Classical Field (and I have my hands full with that, for sure!), but Laurie Anderson has been influential in the contemporary classical scene, so I decided to do a little genre-bending!

In May of last year, Anderson released Homeland, her first solo album in ten years. Her GRAMMY-nominated song, “Flow,” is a meditation for digitally processed solo violin that provides a serene, if melancholy, conclusion to the album’s varied and challenging musical and emotional journey. (You can listen to the song for free at this link.)

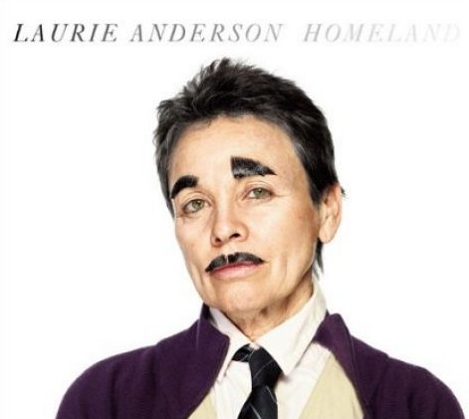

The album’s other tracks explore timely topics, both personal and political, with lyrics and vocal expression by turns tongue-in-cheek: “Should I get a second Prius?” and profoundly heart-wrenching: “The reason I really love the stars is that we cannot hurt them.” Those two lines, by the way, are from “Another Day in America,” sung by Anderson’s alter ego, Fenway Bergamot (so named by her husband and fellow pop icon Lou Reed), who also graces the album’s cover. Formerly known as the Voice of Authority, Fenway comes to life with the aid of a filter that makes Anderson’s voice sound like a man’s – what she calls “audio drag.”

She was kind enough to chat with me by phone recently, and while I didn’t have a chance to ask her about the resemblance I notice between Fenway Bergamot and Charlie Chaplin, our conversation did yield many delightful surprises, including the New Year’s resolution she’s keeping, the two very contrasting composers she’s been listening to lately, and who she really wanted to see playing one of the instruments she built. Click Mr. Readmore for the whole story!

MMN: Your GRAMMY-nominated song “Flow” is so beautiful in its simplicity. Could you tell me about the inspiration behind it?

LA: I think I wrote that on my birthday. I was trying to make a lot of very short pieces. My idea was, there would just be two or three thoughts in each piece. For example, it would move from observation, to doubt, to some other emotion. I was trying to make it almost like talking.

MMN: I heard notes in “Flow” that are lower than a standard violin can play. Is that a five-string violin you’re playing?

LA: It is. It’s technically a viola. It was designed by Ned Steinberger, who does basses and guitars. I contacted him because I really wanted to hit some low notes on the violin. I told him, “It needs another string.”

MMN: So it’s a combination of viola and violin?

LA: Exactly. It’s a weird hybrid.

MMN: When did you begin playing the violin?

LA: I guess I was five. I would saw away as a kid, part of a family orchestra, and I played in orchestras in Chicago. The orchestra just gave me an alumna award a couple months ago. It’s a very nostalgic city for me. I remember certain things, like where the candy store was, where the toy store was.

MMN: Is everything different now?

LA: Yes, but the orchestra rehearsal place is exactly, precisely the way it was. This was a really long time ago – almost half a century ago. And they haven’t changed much. But they have four orchestras now – they have them for little kids, too, which is just great. And they also rotate the concertmaster job, so they try to cut down on the competition, which is really good, because that can really get to kids.

MMN: When you started your career, did you have a particular plan or ambition? What did you want to be when you grew up?

LA: Nobody really asked me that, so I’ve never decided. I still don’t know what I’m doing!

MMN: I’m curious about the electronics you used in “Flow.” Did you use a harmonizer?

LA: I used to use harmonizers. Now I’m designing my own software processing for violin. I was invited by Toni Morrison to go to Princeton to work on any project I wanted, so I decided to try to write some plays. Well, I spent a semester there, and I realized I don’t really know how to write plays, and I never really figured out how.

But I did meet some really interesting students, and one of them was a brilliant software designer, Konrad Kaczmarek. I said, “I want something that string players can use, that accepts the fact that A is sort of A-flat, and B can be sort of B-flat, maybe a little B-natural – something that’s not so strict, and that can move with you.” We had the most fun working together.

As a violinist, you’ve got your head to the instrument, and you’re hearing all of this stuff that the audience will never hear – gritty, crunchy stuff, and overtones and harmonics that are so beautiful. I thought if I could just make those more audible for people, and make it part of the sound – because by the time it gets to the audience, it’s mostly this pure vibrato stuff, and doesn’t have all the other things around the notes that I find really, really beautiful.

That’s what the software does. In this case, it brought up a minor third, which makes kind of a sad cluster of chords to surround the fundamental. It makes the violin not into an orchestral thing, but into something that almost has a little cloud of melancholy air around it, you know?

A couple of things have happened with that little piece. One was, David Harrington from the Kronos Quartet said, “I love that piece; let me make it into a piece for string quartet.” So a few months ago, I spent a couple of days with Kronos, and they played a few different versions of it for me. It’s fascinating how you can interpret things that are not notes. I worked with them on that, and it was pretty fascinating. So we’re going to collaborate more.

MMN: You know, the first thing I thought when I was listening to that piece was, “I want to play this on the organ!”

LA: Oh, really? You should! (Editor’s note: I’ve been working on it!)

The other thing was, Julian Schnabel, the filmmaker and painter, has a new movie called Miral, which is an incredibly beautiful movie. “Flow” is in the film several times, along with another from this series of string works I was doing.

The film is very challenging. It’s about four generations of Palestinian women – you can imagine how hard it is to get it out. But it’s based on a beautiful book that I think is going to find a way into people’s minds. That conflict is… not unresolvable, but so complicated. Julian used the song in situations that are beyond heartbreaking. But he has a way of showing the tragedy of both sides, and that little piece has some of that conflict in it.

MMN: In the liner notes for Homeland, you wrote:

I’ve always felt like a nomad. I travel between many scenes – the art world, the music world, the world of political activism, and the world of books and ideas, never quite fitting into any of them. I love to keep moving.

LA: Yeah, that’s a good description.

MMN: I was trained as a classical pianist and composer, and I remember having teachers who would say to me, “You know, you can’t do everything.” It’s great to see the examples of people like you, who have just followed your inspiration, no matter where it takes you, whatever the genre or the medium.

LA: Yeah, I think it’s a wonderful thing. You know, life is short, and to try to do as many things as possible, for me, has been great. But I can also imagine being a cellist, and never doing anything but playing the cello, and having an amazing life. There are no rules for this.

MMN: I was curious about how you said you never felt like you quite fit into any of those worlds.

LA: I meant, for example, going into the politics of all of those things, and trying to hobnob with the people who do that stuff. That part of those worlds, I’m not good at, and I don’t like it, you know? I mean, I like hanging out with people, but I don’t really like the kind of thing you have to do. You don’t really have to do it, but some people think you do.

MMN: You have been very influential, though, on a lot of contemporary classical composers. And I think perhaps they must have influenced you, too – I’m thinking of people like Philip Glass and John Zorn, people you’ve worked with.

LA: Well, as a young artist, definitely, Phil was my favorite. But I also loved songwriters of all kinds. I didn’t think of myself as being in a world of classical, pop or avant-garde. I thought of myself as being in the world of experimental, I suppose. If there was any place that I did feel at home and still do, it’s in that world.

MMN: And when you got into it, it was really a very new category, wasn’t it Now, it’s sort of institutionalized, which is ironic, given what it is.

LA: Yeah, that’s true. The same thing happened to that as to the avant-garde – time got too compressed. Communication did away with it; you just couldn’t stay ahead of the image-making and sound-making crowd for very long, because people would hear and see what you did, and would become part of it really quickly.

Which is okay, but it doesn’t always happen on the deepest level. If it was just that easy, it would just be ideas that got repeated and expanded. But it’s not actually that easy, because the things that I think are the most amazing works of art – and I’m not saying it makes them better, because I don’t know what makes works of art better, but – things that touch me are what’s happening in terms of the color and emotion of the piece, or movie, or whatever. And that kind of stuff can’t really be copied.

I never felt like I had to stay ahead of what was going on, because it’s not like a trade show. If you see it like a trade show, just inventing new forms, that to me is only a very small part of the picture.

MMN: Is there any music you like to listen to that people might be surprised to know about?

LA: I’m pretty eclectic. I just love that I can download anything. Right now, I’m listening to some Mahler. And Kanye West – I think his new work is just great. Like most people, I’m very across the board, because it’s very easy to get stuff now.

It’s January, and I always start again completely in January. One of the things I want to do this year is listen to a really different piece of music first thing each morning. It’s the time of day when nothing has started, so you can listen to music in a very innocent way. That’s helping me a lot to hear in another way than if I was more awake and critical.

MMN: What is it like to be nominated for a GRAMMY in a Pop category, today, after everything you’ve done in the past?

LA: I’m super-flattered! It’s really not my world; if I were nominated in something more “downtown New York’, I would be less surprised. It’s very nice. I try not to get too attached to stuff like that, but it’s gratifying.

MMN: You’re also receiving a lifetime achievement award from the Society for Electro-Acoustic Music in the United States (SEAMUS) – congratulations on that!

LA: Yeah, thanks!

MMN: That must be very gratifying, too, after all the gear-wrestling you’ve done over the course of your career! I read about your having to give impromptu concerts for security personnel during the course of your post-9/11 travels.

LA: That’s true. It’s just the way the world is now; you carry electronics around, you’ve gotta do free shows!

MMN: Given some of the things that you write about on Homeland, was it difficult to go through that experience?

LA: It makes me angry to have to be searched. I sent an instrument to Chicago, to the Museum of Science and Industry. They had asked me to send them something for their collection. It happened to arrive on the day that George Bush was arriving to give a talk there. Every FedEx package that came into the museum was studied, and mine had batteries and switches and homemade stuff, and looked very fishy. And I tried to get it back, and I’ve never gotten it back.

MMN: Really? Even today?

LA: No, I never have! One of my friends is Salman Rushdie, and he said, “I’m gonna get your stick back! They shouldn’t be able to take your stick.” But he was unable to. I was expecting George to take the stick out and start playing something on it in his final speech, or something.

MMN: Now, that would have been cool!

LA: Wouldn’t that have been great? But it didn’t happen!

MMN: Oh well!

LA: Yeah, Oh well!

__________________________

Miss Music Nerd Recommends:

Laurie Anderson: Homeland