Happy International Women’s Day, music nerds! As luck would have it, I have an outstanding woman to introduce to you today!

Happy International Women’s Day, music nerds! As luck would have it, I have an outstanding woman to introduce to you today!

Gail Archer is a very busy concert organist and dedicated teacher with an impressive list of projects to her credit, including a concert tour going on right now, and a newly released CD, both featuring music by J.S. Bach, part of a project entitled Bach the Transcendent Genius.

I had a wonderful conversation with Gail recently – we talked about church jobs, what Bach and Messiaen have in common, and the ups and downs of being a woman in music, then and now.

It’s a Living… And a Life!

Miss Music Nerd: When did you start playing the organ?

Gail Archer: I had played piano from the time I was 7, then when my legs were long enough at 13, I started taking organ lessons. I learned enough to pull stops for singing hymns on Sunday. So I’d only had about a year’s organ lessons when I started a summer substitute position. I started playing in church when I was 14, and held a church job continuously for forty years, until three years ago.

MMN: That’s amazing! Did you know right away that you wanted to become a professional organist ?

GA: I enjoyed it so much that in my high school years, I played at Cedar Cliffs Methodist Church in Haledon New Jersey, and then worked my way up to a larger Methodist church in Franklin Lake, New Jersey, when I was in college. So I literally worked my way through college by saving up money from my church jobs. It’s just a practical way to make money.

And then I found out that there was a vocation there – wow, who knew? I found that it was my life’s work, and I’ve expanded on that experience by teaching and playing in church, and here I am, forty years later, doing the same things, just on a different level.

MMN: Do you still have a church job?

GA: No, and that’s very new. Three years ago, I became the organist at Vassar College. I go on Friday and teach organ and harpsichord all day long, and I love that. There are two fine instruments at Vassar: a Gress-Miles romantic organ in the Chapel, and a Paul Fritts baroque organ in the Skinner music building. So I teach students back and forth: two lessons on the Fritts, and then two lessons on the romantic organ, so they can study all the literature. And they also have fine harpsichords, so it’s a really wonderful place for keyboard. And then I teach at Barnard and Manhattan School Monday through Thursday, leaving the weekends free to travel, which is really wonderful.

MMN: Right – I was looking at your schedule for the Bach tour, and you’re bouncing back and forth between New York City and anywhere else you can imagine!

MMN: Right – I was looking at your schedule for the Bach tour, and you’re bouncing back and forth between New York City and anywhere else you can imagine!

GA: Yes, most every weekend. I’ll play some other pieces besides Bach, but I certainly am going to play a good deal of Bach this spring, because of the anniversary. I’ll mix in some contemporary music, some American music, other 17th and 18th century composers, but trying to make programs that are relevant and that grow out of Bach’s influence.

MMN: I wanted to ask you about contemporary music, as I’m a composer myself. I noticed that you did a series of Messiaen concerts in 2008.

GA: Yes, that was so exciting. I got interested in his music when I was doing an artist diploma up in Boston, between 2000 and 2002. I went to Paris to work with Jon Gillock – he was a disciple of Messiaen’s. I got very interested in the spirituality in that music: the Gregorian chant and the birdsong, all the influences on him. He was such an innovative composer.

We celebrated his centennial in 2008, and so many musicians were playing his music. It was a rare opportunity to do that kind of a survey. I played on six different instruments all around New York, so that people could hear the color of the music on these remarkable instruments. They were free concerts, so they drew large audiences.

It was a really wonderful artistic as well as spiritual experience. I had to get away from it afterwards, because it was so intense! But it was a really satisfying project.

Bach and Messiaen: Eclectic Internationalists

MMN: That’s wonderful. I think it’s interesting that we’re talking about Bach and Messiaen side by side. They were both deeply religious, and that informed their music. Wouldn’t it be great if they could sit down and chat?

GA: Absolutely. They were highly trained, highly intelligent, life-long learners, and people who were very eclectic. I think that’s what they have in common. Messiaen traveled all over the world – in the modern age, he could do that. Bach’s life was not like that at all; it was much more difficult in the 18th century.

But Bach brought the world to himself by studying the international styles. He bought Italian scores and French scores. He learned what Vivaldi and Frescobaldi were doing in Italy, and what Lully was doing in Paris. He was Lutheran, so he based much of his music on hymn tunes, inspired by the poetry of Martin Luther. But that didn’t prevent him from looking at what the French and Italian Catholics were doing. He created his style from a whole great pot of resources. He learned by studying and copying the structure of the international styles of his period, and creating this great synthesis: a universal style of the Baroque.

And Messiaen did the same kind of thing. He was raised as a French Catholic, but he was interested in the mysticism of the East: he studied Hindu rhythms and melodies. He looked at the natural world for inspiration… So he was also a very eclectic composer, putting Gregorian chant together with Hindu rhythms, and then all of the natural resources.

So their methods were very similar, and they were both highly trained, highly intellectual, structural composers. They have a lot in common as well as deep spirituality, one Catholic, one Protestant.

MMN: That’s fascinating.

GA: Yeah, I think it is really fascinating. They were both great borrowers, trying to get the best of many different traditions, and making it their own in the end.

MMN: Was Bach unusual for doing that sort of thing in his time?

GA: Handel did it, too, but approached it differently. Handel did have a chance to travel. He was born in Germany, but spent four years in Italy in his 20s, and eventually went to England. He spoke many languages: his native German, but also fluent Italian, and he wrote all his personal correspondence in French. Then, at the end of his life, he became a naturalized British citizen, so he spoke English, too. Bach never traveled internationally, but he studied the music of other countries.

MMN: Have you ever programmed a recital with both Bach’s and Messiaen’s music?

GA: Yes. In fact, there are two pieces based on the same text, from Acts 2: “There came from Heaven the sound as of a mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting.” It’s the text for Pentecost, fifty days after Easter. Bach wrote a piece called “Komm Heiliger Geist,” “Come, Holy Ghost.” It’s the very first of the Great Eighteen Chorale Preludes. And then the very last piece in Messiaen’s Mass of the Pentecost is based on exactly the same text. So I have programmed those two pieces on the same concert. Both composers were looking at those same words, and saying, “What is it like to have a house filled with a mighty wind?” They respond to it in a very similar way, but with different harmonies. It’s really wonderful music.

MMN: I understand that Bach was not appreciated as a composer in his lifetime – he was more appreciated as an organist.

GA: Yes, very definitely. He was appreciated as a great improviser. He actually went around and tested organs. A church would put in a new organ, and have Bach in to test it, to see if the wind was strong enough, or if the reeds had high enough wind pressure, or if the organ sounded well in the space. He wrote detailed reports that are really amusing to read. He knew as much about building organs as he knew about playing them, and he was very famous for that. He was less appreciated as a composer in his lifetime; all of that came long after.

For Once, an Old Girl’s Network!

MMN: Through Mendelssohn, who you have expertise in as well.

GA: Yes, absolutely. That was my project in 2009, looking at Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms, Max Reger: composers who were inspired by the Bach revival. Mendelssohn conducted the famous performance of the Saint Matthew Passion in 1829, and the piece hadn’t been heard in about a hundred years.

Mendelssohn did not conduct the whole thing; he truncated it in a brilliant way. There’s a book by Jeffrey Sposato, very recently published, that shows how brilliantly Mendelssohn culled the kernel of the piece, without losing the most vital aspects of the narrative, both the story and the music. That abbreviated version of the Saint Matthew Passion was performed frequently in Germany in the 1830s and 1840s, and sparked interest in Bach and Handel in the 19th century.

I also played some of Fanny Mendelssohn and Clara Schumann‘s music, too. They wrote a little bit of organ music, and I included that, because it was harder for women to have their music heard in the 19th century. They were all encouraged to marry, have children, and stay home. They didn’t mind doing that, but they also wanted careers that were meaningful, and to be able to use their ability.

MMN: They wanted it all!

GA: And those women succeeded in doing that.

MMN: It’s always interesting, and sort of heartbreaking, to study those women’s lives.

GA: Absolutely. And what’s also interesting that I learned in this last year, is that the connections between Bach and Mendelssohn actually came through the women of Mendelssohn’s family. Mendelssohn’s great aunt, Sarah Itzig Levy, was a personal friend of C.P.E. Bach. She was a wonderful harpsichordist, on the professional level. She had a manuscript of J.S. Bach’s that she got from C.P.E. And Lea Solomon, Mendelssohn’s mother, studied piano with Johann Philipp Kirnberger, who was a student of J.S. Bach.

MMN: I never learned about that in music history class!

GA: Well, there you go! I didn’t it either. I found out by reading lots of biographies and putting the pieces together. When I figured it out, I yelled, “Oh my goodness! Look at this!” It was eye-opening.

The Stained Glass Ceiling

MMN: Do you mind if we talk about what it’s like to be a woman in the organ world today?

GA: That’s an interesting topic. That’s probably the most challenging issue I face all the time, because one has to work four times as hard as one’s colleagues to make half the progress. That’s just the way it is.

There was a wonderful article by Nicholas Kristof in the New York Times talking about the elders: Jimmy Carter and Archbishop Tutu and Nelson Mandela, some of these remarkable former leaders of nations who are trying to do good in the world. They were talking about feminism and religion, worldwide, that all religions of the world place women as 2nd-class citizens, and how that desperately needs to be changed.

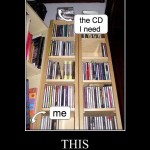

And that’s why women organists have a tough time, because most of the clergy of the world’s great religions have traditionally been men, and that makes it pretty tough for women to obtain cathedral organist positions. I applied for the major church jobs in New York for ten years, and never even got an interview. Nothing at all. And watched the positions go to those who’ve had much less experience and expertise all the way around than I do. So I had to give up, and just go with some college work, because it was the only way to make forward progress.

It’s just been run in such a conservative way for such a long time: older gentlemen bringing along the next round of young people, perhaps forty, fifty years younger than they are. But women with DMAs and PhDs who can conduct and compose. It’s not just me. There are many women who have remarkable skills and can do so many things well, and they are almost ignored. You have to do so much to get attention, because the culture of the organ world generally is to celebrate people who are older, or to bring along students who are much, much younger, who are celebrated as prodigies.

So for women in their 40s and 50s, the challenges are enormous. You’re just working and working and working, and people say, “Well, that’s pretty good.” Pretty good? My gosh, I hardly sleep! Are you kidding me? You really have to have a sense of humor.

I think women clergy are facing these issues too, and for the same reasons, in all the denominations that ordain women. Even in those that have been ordaining women for thirty or forty years, those women still can’t break into being the chief pastor in a big church. They can’t. They can get a smaller parish, but they can’t be on Fifth Avenue in New York – even though they’re brilliant speakers, brilliant theologians. It’s really hard.

MMN: Wow… You think of that happening to actresses in Hollywood, but it’s really kind of pervasive, isn’t it?

GA: It is. I’ve been threatening to put up a website for women organists – I started to do it two years ago, but these various creative projects have taken over, and it’s so hard balancing. This is the trouble for women – we’re all balancing so much. Many of us have families. The women are shouldering a double burden, and I know it’s not just in music – it’s everything. You might be married or have family, then you’ve got two or three jobs. Then you’re trying to do the creative piece on top of it, and you’re trying to do advocacy on top of that. It’s hard to sleep!

So I am working on a website that will advocate for women organists, for these very reasons. There’s such a lot to celebrate, and the women are just pushed aside and ignored, or their accomplishments diminished. It’s truly unfair, but you just have to persist and keep doing good work, and keep a positive outlook, speak kindly of everyone, and just keep moving forward. It’s really the only thing anybody can do – just try to be positive, even when you’re discouraged.

MMN: That’s great. This website you mentioned – is it up yet?

GA: No, it’s not live yet. I’ve called it Women on the Bench. We’ll see what happens.

MMN: I look forward to it!

Fools rush in where angels fear to tread…

I’m thinking hard of a way to put this…

I see a tightly-knit community of men who are just more inclined to notice, delight in and champion the work of other men, and who who are just more inclined not to notice, delight in and champion the same package of talents and skills in women. This phenomenon and dynamic renders women practically invisible. There are to a greater or lesser degree similar communities in the ordained ministries of some denominations that function in largely the same fashion. This community might not esteem itself to be gender-biased, but I think it is pretty obvious and to tell the truth natural, considering.

Boy, am I gonna get it ,'(

mcdoc, I agree with you — I assume that phenomenon is amplified by the religious setting where women aren’t recognized in other senses as well. (My perspective: young composer working almost exclusively in the secular / concert music world.)