Thus far we’ve concerned ourselves with the preparation of a pretty score, a thing of beauty that will be a joy forever, suitable for publication as a coffee-table book, not to mention indispensable to the conductor. Now, what about the people who really matter, the lifeblood, heart and soul, and worker bees of the orchestra — the players?!

You could try handing a full score to each player, but pretty soon you’d have wind and brass players shooting poison darts at you through their mouthpieces, and string players using their bows for shooting arrows instead of making strings vibrate. And you don’t even want to think about the kind of blunt trauma the percussion section could inflict… composition can be dangerous! 😉

Fortunately, your music notation program will create perfectly formatted, camera-ready individual parts with the click of a mouse!

And if you believe that, Mr. Readmore and I have a bridge to sell you. 😛

It’s true that Finale will separate each instrument’s line into a separate file for you. It’s called “part extraction,” and you don’t even need a local anesthetic to perform it. You do need to spend some time with each part, troubleshooting, beautifying, primping and polishing it to a fine sheen, though, before you can present it to the players with any hope of a positive response.

Oh sure, you can manipulate several different parameters before you extract the part, by navigating through an impressive series of dialog boxes:

But I don’t care how careful you are in telling the program how to set the page and system margins, how many measures to fit in each system, etc. etc. There are some things — make that many things — that require the tender ministrations of a musically intelligent human. Especially if said human wishes to avoid the wrath and disdain of those all-important orchestra members.

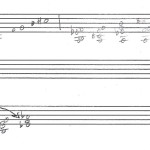

Here’s a page from the cello part, fresh from the magic part-extraction machine:

Before:

It’s a perfectionist’s playground! Lots of little things are being squished together, and need to be given some breathing room!

After:

Ah, that’s better… In addition to fixing the various spacing issues, I replaced the title at the top of the page with the instrument name, just in case one of the cellists is married to one of the bassoonists, say, and they get their music mixed up. (It could happen, you know!)

Notice that horizontal bar with the number 7 above it at the bottom of the page? That indicates 7 measures of rest for the player. It’s called a multimeasure rest — see, some things in music are nice and logical!

The position of that particular multimeasure rest at the bottom of the page is no accident, by the way, and it brings me to what are perhaps the most important aspects of creating the individual parts:

Page turns

and

Transposition

That first item has to be carefully managed by a human, as it involves finding the rests and arranging the distribution of measures and staves such that the rests land in just the right places, while the measures containing music remain well-spaced and legible. I’m not aware of any computer program that can do that at present… maybe someday!

The second item is very easy, as long as you remember to do it.

Oh, what do I mean by transposition, you say?

Certain instruments sound in a different key from where the music is written. The reasons for this have to do with the physical/mechanical construction of the instruments as they developed way back in history. For example, it used to be that you had to have a different horn for each key you wanted to play in — pretty impractical, not to mention expensive for the horn player! Nowadays, there is one horn that does it all, but it’s still a transposing instrument, because it turns out that the Horn in F had the nicest sound.

If the above reads like gobbledygook to you, don’t worry; as a pianist, I find the whole transposing concept mysterious and satanic. All I have to do is remember to write the clarinet part a whole step above where I actually want it to sound, and everything is hunky dory.

I mention this because of the one horrible time when I forgot to do this. It was while I was in my master’s program at NYU. I showed up for a first read-through of a piece, woozy from 2 hours of sleep after a very late night spent getting my parts ready. When the music started, anyone listening might have concluded that the clarinet player was drunk. In fact, it was all my fault. And believe me, players do not take kindly to being made to sound bad. There was nothing for it but to take my lumps and put on a brave yet contrite face, until I had the chance to go home and cry. (This is just one of many reasons why I NEED A LAPTOP! Actually, this is one of the more convincing reasons; would you believe that some people think blogging in bed is a frivolous desire? 😛 )

I told McDoc the above story, and asked him to remind me to double and triple check that I had all my transposing ducks in a row before I sent off my parts. He made sure I couldn’t forget:

And, happily, I did not. Well, wait, lemme go check the parts one more time, just to make sure…

Heh.

That concludes this series on music copying… though I’m sure I’ll have more to share about it in the future. For now, I’ll leave you with some final thoughts on the matter, in the form of…

Miss Music Nerd’s 7 Tenets of Music Copying

- The composer will always miss the deadline for finishing the piece. Even if the composer is you. Especially if the composer is you.

- The copying/editing/proofreading process will take three times longer than you expect, even if you account for it taking three times longer than you expect. (See also: Hofstadter’s Law.)

- Your perfectionism is your best friend and saving grace. At some point, though, you have to turn it off and declare the project finished.

- The music copyist who proofreads her own work has a fool for a proofreader. But who can afford a proofreader?

- Software programs think they know what you want and need. They don’t.

- There will come a point during the process when you will want to throw the computer out the window. Later, you’ll be glad you resisted this impulse.

- Don’t forget to transpose!!!

…and last but not least:

If you enjoyed this post, would you consider…

Thanks — you make the world a better place! 🙂

Thanks for this series. As a church musician, I don’t get too many chances to present original works, but I am constantly making scores of ‘arrangements’ for a variety of ensembles with widely divergent levels of musicianship. Perhaps semi-pro and professional players can be expected to count long sets of measures and confidently enter, but a cautious copyist might choose to include cue notes after long breaks. Also, depending on the way the piece starts (upbeats, pick-up measures, single instrument or full ensemble), I’ll make sure the cueing is crystal clear.

It’s all so very true.

And there’s now way to please all musicians who use the parts you generate.

I used to produce parts for a chamber orchestra I played in. I found that, no matter how accurate your are in note entry or how much time you spend getting the layout just right, there will be some [expletive deleted] who will find a nit to harp on. Not to mention the harpsichordist and violist who, just before a performance, change the harmonies you so carefully entered. I remember thinking a particular “where the heck did *that* bit of Ives come from” in a Vivaldi performance.

You get an enormous amount of respect from me for your work.