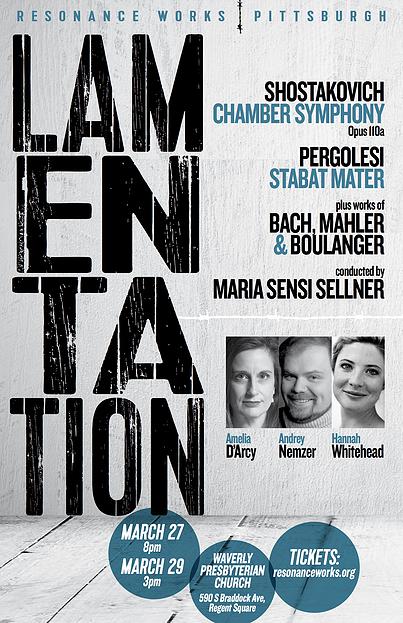

One more performance of this program this afternoon, Sunday March 29, at 3pm! Click here for more info and tickets!

It’s not every day you hear J.S. Bach and Gustav Mahler on the same concert, let alone adjacent on the program order. Last night, Pittsburgh performing ensemble Resonance Works demonstrated that perhaps it should happen more often.

This uncommon pairing was just one of many intriguing elements on a program entitled “Lamentation.” The selections spanned a wide range of instrumentation, musical style, and historical context, and each one illuminated the central theme of expressing grief or sorrow in its own distinctive way.

The program began with a quintessential embodiment of the lone, plaintive voice in the form of two movements from Bach’s Cello Suite no. 5 in C minor, performed by Hannah Whitehead. The Allemande is punctuated by triple and quadruple-stop chords that create an almost stately melancholy, but the Sarabande that followed shifted into desolate solitude (as conductor Maria Sensi Sellner mentions in the program notes, it’s one of the few movements from the cello suites that is purely a single line, with no chords). I almost wished the Sarabande had stood alone as the opening solo, to make the transition into the ensemble music that followed even more sharply defined.

With the final notes of the Sarabande still faintly reverberating, conductor and chamber orchestra proceeded seamlessly into “Erbarme dich, mein Gott,” sung by countertenor Andrey Nemzer. This alto aria from Bach’s St. Matthew Passion reflects Peter’s remorse after denying Jesus, but the text transcends its context and expresses contrition as a broader human experience. The ensemble’s interpretation of Bach was richly expressive, and I wondered if early music enthusiasts might find it too romantic. Nothing’s too romantic for me, though, so I luxuriated in it.

That approach also helped with the transition into Mahler’s Adagietto for strings and harp, his ardent, anguished musical love letter to his wife, Alma. Somehow, the transition from a lament of penitence to a lament of love didn’t seem at all disjunct. I was curious to hear how the Mahler would work with a small chamber ensemble — three first violins, two each of second violins, violas and cellos, and one bass — rather than the dozens of strings typically used in a Mahler symphony. One immediately evident benefit: I could actually hear the harp! In the places where the dynamic is soft and the texture is sparse, the music became wonderfully delicate and intimate. And when it came time for the swelling, sighing, climactic suspensions essential to the impact of the piece, there was nothing lacking. I’m not even going to pretend I had something in my eye, because anyone who knows me knows that piece gets me every time — no matter the size of the orchestra, I now know.

Before each piece, narrator Anna Singer offered related readings — a quote from a poem from Mahler to his wife, for one. The reading introducing Lili Boulanger’s setting of Pie Jesu was from Leonard Bernstein’s account of a conversation with Lili’s sister Nadia as she neared death:

“I heard myself asking: ‘Vous entendez la musique dans la tete?’ (Do you hear music in your head?)

Her instant reply:

Tout le temps. Tout le temps. (All the time. All the time.)

This so encouraged me that I continued, as if in quotidian conversation: ‘Et qu’est-ce que vous entendez, ce moment-ci?’ (Do you hear it now, at this moment?) I thought of her preferred loves. ‘Mozart? Monteverdi? Bach, Stravinsky, Ravel?’

Long pause.

Une musique… ni commencement ni fin… (A music… without beginning or end.)

She was already there, on the other side.”

Lili died prematurely, only 24 years old, and dictated her Pie Jesu to Nadia when she was too weak to write herself. Nadia remained devoted to Lili’s memory and music as she lived into her 90s, becoming a legendary teacher whose students included the major composers of the 20th century. It was very fitting, and moving, to connect the last moments of Nadia’s life with Lili’s setting of the words, “Grant them eternal rest.” Soprano Amelia D’Arcy sang from high above the altar, in the loft next to organist H. Preston Showman, underlining the angelic, ethereal quality of Boulanger’s music.

The lamentation theme took a sinister turn with Shostakovich’s Chamber Symphony for Strings in C minor, an arrangement of his String Quartet no. 8. The piece expresses his bitterness and shame at being forced to join the Communist Party in 1960, feelings so intense that he contemplated ending his life, and thought of this piece as an elegy for himself. It incorporates an abbreviation of his name translated into notes: D-S-C-H, corresponding to the notes D, Eb, C and B. It also quotes from some of his earlier works as well as the famously ominous Dies Irae chant from the Requiem mass. Certain parts of the piece evoke dread overtly, like the thrice-repeated chord in the fourth movement that, as the program notes describe, is like a cross between the opening motive of Beethoven’s 5th Symphony… and gunshots. The second movement quotes a theme from his second Piano Trio that I’ve always heard as a wacky, demented Russian hoedown, but in this context it was hair-raising, like Bartok in hell. But the truly frightening moments were the quieter ones, where an ominous background drone pervades as mournful string melodies flail helplessly above it. It was abolutely terrifying and I loved every minute of it.

And that was just the first half! Pergolesi’s monumental Stabat Mater formed the second half. More on that later, as I want to get this posted before the second performance of this program has passed.

Resonance Works is a terrific newer company in town that deserves a wider audience.